The Art Agenda: Soft Power Strategies and the Rise of Russia

For centuries arts and culture have been used by governments as a tool to achieve a better understanding and interaction with other countries. In recent years of fast globalisation, an effort to promote local culture on a global scale (without force or threats) has been referred to as “soft power”. However, the extent of governments involvement in this process has varied from country to country.

One particularly interesting example that demonstrates both successes and failures of the government’s extensive use of soft power is contemporary Russia.

When Vladimir Putin became Russia’s president in 2000, among his first instructions to ministers was that soft power would now be one of the main instruments by which the country would exercise its global power in the 21st century.

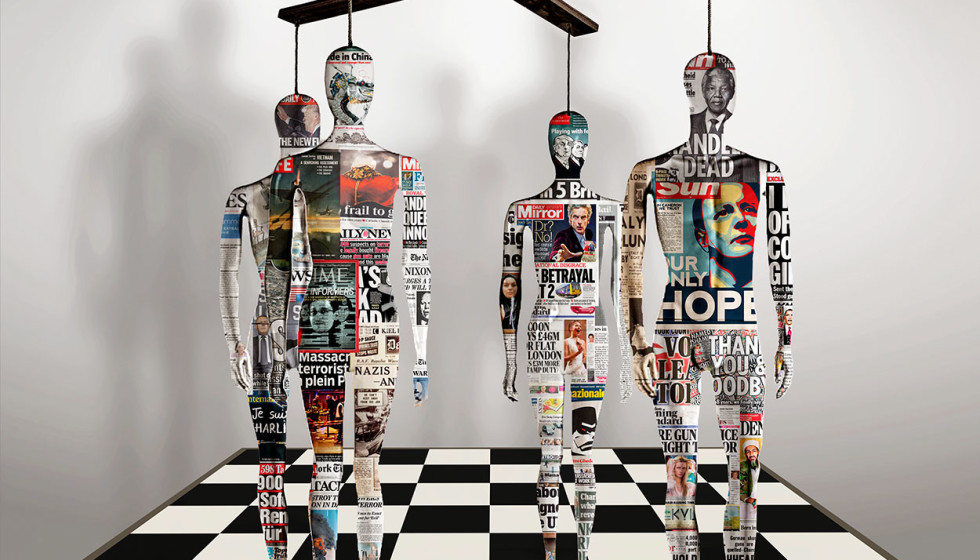

The Kremlin was turning away from decades of aggressive Soviet ideology, but the new policy really reflected Russia’s weakening position among the major global powers. After the Soviet Union’s collapse in late 1991, the remainder of the 1990s in Russia was a time of unprecedented social and economic change. In the 2000s the Russian state had very few opportunities to exercise power effectively and the political elite decided to ‘weaponise’ the country’s national art and culture to help achieve its foreign policy goals. As Groys has explained in his study: “Art becomes politically effective only when it is made beyond or outside the art market- in the context of direct political propaganda”. (Groys, 2013, p.7)

As in most European nations, main public museums in Russia are financed by the state, which means they are subjected to the Ministry of Culture. Therefore, it’s no surprise that the state is able to influence how museums are run, especially determining artistic and intellectual programming and curatorial policy. The State Hermitage Museum in St. Petersburg, is one of the oldest and largest museums in the world, founded by Catherine the Great in 1764. Its collection comprises over 3 million artefacts, but of this total number, only a small percentage are on display. Thus, the museum has plenty of ‘ammunition’ in the form of this vast treasure trove: items that can be used and displayed in exhibitions around the world. Therefore, State museums can be seen as potential ideological weapons in the Kremlin’s arsenal. Accordingly, when the Hermitage Museum plans any international activities it should be viewed as part of the state’s efforts to project power abroad.

The Hermitage Amsterdam programming is an excellent example of Kremlin using art as a weapon to develop Russia’s foreign relations. It gives an indication of Russia’s agenda – a fondness for the Imperial court of the tsarist era. One might even say that the goal is to promote the idea of autocracy. Trying hard to diminish the image of the Soviet mentality in the eyes of the West, Putin tries to enforce the image of the once admired Great Imperial powers. It appears that Putin himself wants to be seen as a grandest force that needs to be constantly admired. In his efforts of being liked and remembered he takes up many of Hitler’s tactics. Boris Groys in his book “Art Power” gives a insight into Hitler’s “The Hero’s body” when describing how Hitler did not want to observe instead he wanted to be observed, admired and idolised as a hero (Groys, 2013, p.135). Groys explains that “the creation of heroic race, for Hitler, can be admired in the monuments of the heroic bodies that belong to that race” (Groys, 2013, p.139). It had proven to be very effective in Hitler’s pursuit of mortal fame until it became total infamy. Putin’s approach is similar, until it becomes a disgrace due to political and social events such as Russia’s annexation of Crimea in March 2014 and the shooting down of Malaysian Airlines flight MH17 in July 2014, supposedly by Russian-backed rebels in Ukraine, killing 193 Dutch citizens on board.

However, if we only evaluate how effective this exercise of soft power has been we can see a slow but consistent progress of opening various nation’s hearts towards Russia’s arts and culture. “Viewers may disapprove of the cultural values of the show, but still enjoy watching it for entertainment purposes. There is not necessarily a correlation between consumption of media and an ideological effect” (Movius, 2010, p11). First, the museum’s popularity and attendance have been consistently strong. “In the Hermitage’s branch in Amsterdam there was an exhibition devoted to the last Romanovs,” said Hermitage director, Mikhail Piotrovsky. “People came away from it crying. We did not think that it would arouse such interest” (Izvestiya, November, 2016).

Second, it’s also worth taking a look at Hermitage’s recent activities in Italy. Italy is a NATO country, but one with which Russia still enjoys very friendly relations. In 2007, the research and culture centre, “Hermitage-Italy,” was established in the city of Ferrara to conduct joint research that focuses on collections of Italian art and Russian-Italian relations. In 2013, the Hermitage-Italy Centre moved to Venice, and since then it has been housed in the Procuratie Vecchie on St. Mark’s Square. The centre’s “main tasks include conducting research for cataloguing of the Hermitage collections of Italian art; as well as establishing a documentation centre on the history of Italian art collecting with regard to the Hermitage collection.” (State Hermitage Museum, 2018). There is also the approximate $38 million Hermitage-Barcelona that is planned to open in 2019. This will bring Russian ‘soft power’ to Spain, another NATO country that has long been a favourite place for wealthy Russians. “The museum will have five floors and seven gallery rooms, distributed over 15,000 square meters, and is expected to receive up to 500,000 visitors per year” (Art News, June, 2016).

Considering the above, President Putin has been using soft power somewhat successfully. However, with the constantly increasing political tensions, both internally in Russia and externally with most of the Western world, it is questionable whether such an approach has any likelihood of long term success. The popularity of individual exhibitions is not enough to make the public opinion look more favourably on the government’s state policies. Nevertheless, it is undeniable that such efforts will certainly continue and that Russia is planning to use soft power in the long term, which, perhaps, will test its long term capabilities of using art and culture in order to achieve political goals.